I recently felt an urge to return to one of my all time favorite video game series: Metal Gear Solid. It had been years since I revisited the earlier titles and a few of them were only available on my PS2. I decided to update my library and purchased the Metal Gear Solid Legacy Collection for the PS3, which includes:

- Metal Gear

- Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake

- Metal Gear Solid (digital voucher)

- Metal Gear Solid: VR Missions (digital voucher)

- Metal Gear Solid 2: HD Edition

- Metal Gear Solid 3: HD Edition

- Metal Gear Solid 4 Trophy Edition

- Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker HD Edition

Regardless of your feelings toward Hideo Kojima’s fever dream/magnum opus, it’s difficult to argue against the significant impact the series has had on video game evolution and experimentation. To this day each game remains exceptionally playable, despite some rough edges and performance setbacks. The earlier titles may have aged, but they’ve done so with a charming grace that makes a return to the older games an enjoyable experience. My recent playthroughs showed me that my expectations were not simply based in nostalgia. The lasting impression that the series has had on me likely stemmed from the Kojima’s creative directing. The core games make the most out of the technology they are featured on without implementing systems that become obsolete on the arrival of the next generation

Dated but Not Forgotten

The original playstation version of Metal Gear Solid, for example, brings the player into an expressionless snowstorm of polygons, where the mechanical nuances of the series are thoroughly absent. Still, the general consensus insists that it’s the preferred way to experience the start of the “Solid” saga. The Nintendo Gamecube remake Metal Gear Solid: Twin Snakes is typically seen as a hard departure from the original style and atmosphere, even though it adopts the advanced game mechanics from Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty.

What exactly does this tell us? Is it pure nostalgia that drives some fans to stand by the original version, and put up with clunky controls and dated visuals? To me, the message reads loud and clear that there are much more important elements at play when it comes to the Metal Gear games. When MGS first released there was nothing else like it. Games were exploring new frontiers and playing the the tools that were available on the 3D consoles, but none quite hit the mark that Kojima did. This was a brave new world where cutscenes could last ten minutes, and still manage to keep the player attentive the entire time. In every nook and cranny of the Shadow Moses complex there were small easter eggs to discover, left there by the director himself. A majority of these features were experiments with the sole purpose of discovering what could actually work, or simply be entertaining a video game.

This inspired, artistic direction is really what shines throughout Kojima’s Metal Gear franchise. If you take a trip back to the old MSX/MSX2 titles, Metal Gear and Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake, it’s easy to see how much time was spent on instilling new concepts. While the games were in many ways bogged down by burdensome mechanics, they were constantly treading in uncharted waters. The foundation of the early Metal Gear games was similar to other popular titles of the time. The top down, free roam view of Zelda, and the backtracking exploration of Metroid show clear similarities.

The fascinating aspect of Metal Gear was how Solid Snake reacted with the environment. Each new map area had its gang of roaming enemies where Instead of just instinctually attacking you the moment you entered their vision, they would set off an alert that put the rest of the enemies into a shoot first ask questions later frenzy. These enemies didn’t even have to be in your current arena to launch into the “alert” phase, and running into the next room would bring the angry soldiers with you. At this point the player is forced to decide between hiding, or eliminating the entire squad until the radar goes back to normal and allows them to clip back into stealth. This pattern continues until it’s interrupted by a unique boss fight that calls for a variety of gameplay approaches to defeat. A common approach is to stop, mid battle, and contact different members of your mission squad on an inner ear radio, iconically named “Codec.”

Prattling on about these mechanics in 2018 is hardly as impressive as it might have been in 1987. You really have to consider the sheer audacity it took to unleash something these components, through a form of media that was nowhere near as prominent then as it is now. These systems could have been a complete bust, putting franchise belly up before it ever had the chance to blossom. Instead, they influenced the standard of video game design for years to come.

Leaps and Bounds Forward

Where Metal Gear Solid set the stage with narrative quality and unique approaches to gameplay, Metal Gear Solid 2 pushed those barriers even further. Kojima’s main protagonist bait and switch may have been a negative aspect for die hard fans of the OG Solid Snake, but the subsequent thrill of the Big Shell Incident was anything but disappointing. MGS2 brought a plethora of features to pine over, many of which determined the direction of the series. At the time of its release, the Playstation 2 was the epitome of console gaming. The graphical capabilities of the system carried the MGS franchise to the standard that it probably should have started at. This is obvious from the basic visuals the game presents, but more so through the smaller details that you will pick up on as you progress.

The first time I played MGS2 I was blown away by the sound effects and mixing. Each character on screen had this unbelievable realism when reacting with the environment. Boots hit metal with a reverberating “clap.” Magazine reloads came with a series of clicks that could only be described as satisfying. The longer I played, the more I would notice things like Snake’s bandana flourishing in the wind as he opened one of the tanker doors to travel outside. After finishing a firefight with a group of guards I would find the ground littered with shell casing that matched the exact number of shots fired by both sides. The fluorescent lights on the ceilings reflected on the glossy floor below. I’m now seeing all these things in 2018 and it still blows my mind that it existed in a video game from 2001.

Where the Big Shell in Metal Gear Solid 2 was this pristinely manufactured new age fortress on the Hudson river, Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater took a different approach by exploring the jungles of the USSR. The third entry in the Solid series objectively covers past events through the perspective of a young Big Boss (Solid Snake’s genealogical father). I don’t have time to go through the story synopsis here. If you’re looking for a bit of light reading, hop on over to the Metal Gear Wiki for a story that’s just as confusing and anime influenced as the Kingdom Hearts series. The main point I’m trying to highlight here is that Metal Gear Solid 3 was a perfect next stepping stone following the impressive sequel that was Metal Gear Solid 2. Rather than try to showcase what the near future of present day would look like, Kojima took us back to the cold war days to fill us in on all these questions that have been ruminating since the beginning of our adventure with Solid Snake. The main question at this time was likely: “who the fuck is Big Boss?”

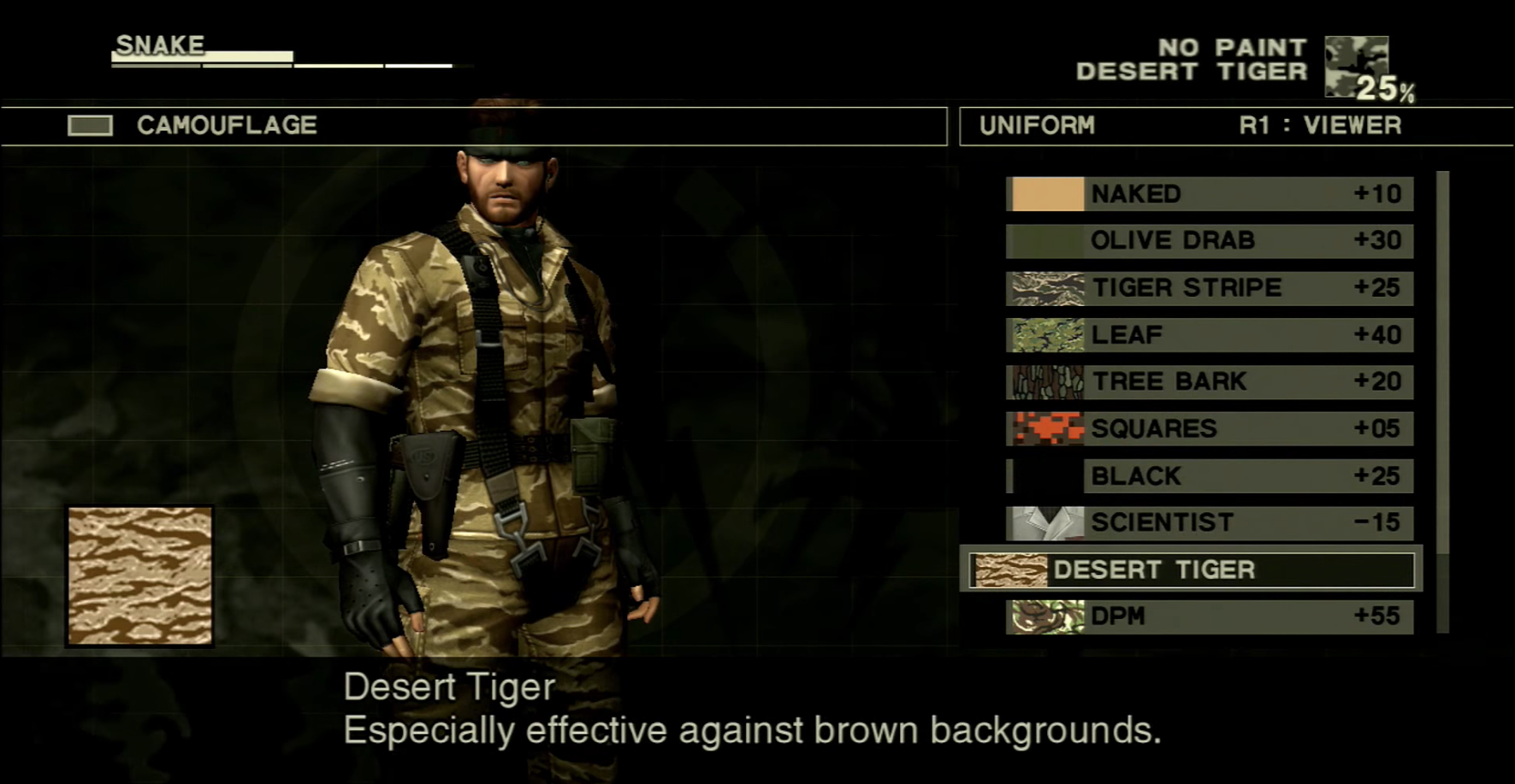

In MGS3 we found out exactly who Big Boss was. We also found out that taking these stealth mechanics into a jungle warfare scenario fit like glove. Rather than place the focus on implementing a myriad of new tricks the player could keep busy with all the way to the finish line, the focus was shifted to a new environment for the player to use to their benefit. With this environmental foundation came the extensive customization feature as well. Snake could now be outfitted with the perfect combination of disguise gear to make his presence as subtle as possible. On top of this was a newly survival system that the player would need to maintain throughout the game, including hunger management and manual healing for the various injuries Snake naturally gathers along the way. There was now this extensive playground to explore that had been absent from the series thus far, giving Metal Gear Solid 3 its uniqueness, to ensure that it would stand out years later. These experimental mechanics went on to influence both Metal Gear Solid 4 and Metal Gear Solid 5 in very significant ways. At the same time, MGS3 introduced fans to a new world that had only existed as urban legend. While the branching stories of Solid Snake and Big Boss are both part of one cohesive universe, each is exceptionally interesting in its own way.

I Can Do Anything Better Than You

With all the love I give to the Metal Gear Solid series, I have often found myself frustrated with the finicky nature of the first three games. The controls were vastly improved in MGS2 and MGS3, but there was still a level of discomfort. The complex control schemes did not cater well to the player once the shit started hitting the fan. Camera angles were unforgiving too. Similar to the quirky “room corner” perspective in the early Resident Evil Games, the camera typically stayed fixed in one angle, regardless of the direction your character was walking (this was changed in the Subsistence edition of Metal Gear Solid 3). Whether these things were intentional is beyond my knowledge. Knowing Kojima, it’s very likely. Once Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots hit the scene, most of these frustrating mechanics were left behind for a much more contemporary gameplay feel.

I can’t say for certain that Kojima was attempting to adopt some of the styles that had grown popular through next gen consoles, but it certainly felt that way. Maneuvering Snake was more comfortable than it had ever been. Camera angles were no longer a hindrance and actually gave the player beneficial perspectives to work with. More importantly, MGS4 included more gadgets and tools than ever before, allowing the player to push through its various chapters in the style they saw fit. Furthermore, MGS4 stepped into the new age with the same level of individuality as its predecessors. Borrowing from every available aspect of the series thus far, Guns of the Patriots was something truly unseen at the birth of the Playstation 3. Arguably more of a movie than a tactical espionage action game, the narrative themes were turned up to eleven for the conclusion of the Solid Snake saga.

MGS4 definitely broke ground in the variety it offered, and this was only expanded on with Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. Taking a very different approach compared to MGS4’s extensive cutscenes, MGSV focused primarily on gameplay and built on the adaptable systems of the previous title. Rather than lay out a direct storyline and goal to follow, MGSV presented the player with a various missions and management systems. The charming appeal of this format is how unbelievably broad playstyle application becomes once the chains are loosened. Updating loadouts and planning for missions interestingly flips the Metal Gear coin over to the other side and reveals what the series is capable of when straightforward tactical espionage is not the only way.

Whether You Like It or Not

This article might sound like your standard love letter to a game developer. I’m fully aware that the Metal Gear Solid series can come with a polarizing fandom. On one hand there are those who defend the genius of Hideo Kojima with a brick wall mentality, and on the other there are those who see Kojima as aggressively self indulgent. I think both of these points are worth defending. When you look at the series as a whole it’s easy to identify the broad impact that has been left in its wake. At the same time a critical analysis will point out some of the contradictory inclusions that happen from title to title. Keep in mind that oversight and overlap is to be expected in this medium. You can’t always directly compare video games to film or television, yet they often set out to achieve similar goals. Kojima’s obvious influence from the film industry is littered throughout his franchise, which can border on derivative more times than not. Still, it’s his conviction to spinning this tapestry of intrigue that is all the more impressive the further we move down the road. Here I am at 28 years old, watching the games of my adolescence rust and show their flaws, yet Metal Gear Solid remains one of the most overwhelmingly significant sources of imaginative expression I have ever seen. It’s something that wasn’t able to be carried over into Konami’s first Kojima-less metal Gear game, and it’s something that I’m expecting from the Death Stranding once it releases.

I approve of this article. MGS games have a very special quality to them in how they take these gigantic stories and make them feel very personal. To be clear, I don’t mean it in the sense that we connect personally with the characters. It’s a series about super soldiers, robot ninjas, and giant nuke wielding mecha after all. However, playing these games gives you a sense of who Hideo Kojima is and what he finds entertaining or interesting. It’s like watching a movie with a friend that has all the same reactions as you. You both find that explosion awesome, or that character fricking cool as hell.

Games can be an impersonal medium at times and they often feel generic and faceless. MGS stands as a stark contrast oozing personality out of every pixel. I can’t wait to see how Kojima tells us his next story.

Great article worth the read and well written. Author really goes in depth and picks apart the games.

I agree. On paper a lot of these elements fell like tropes (because they kind of are), but the flavor from the director is apparent at every moment. Thanks for reading and leaving your feedback!

Thanks for reading! Glad you enjoyed it.

Great read. Im old enough to have experienced the NES version at about the age you were when you likely played mgs2 for the first time. While Kojima hates that port, it is still, undoubtedly, metal gear. I wasn’t lucky enough to have played Silas Warner’s “Wolfenstein ” games until much later, so that was the first time the objective wasn’t “blast everything indiscriminately”. I’ve been hooked since. Other games may do stealth better, but NONE of them have an ounce of personality when compared to those games. You didn’t talk about bosses reading your memory card or having to reset the console lol. Remember when you figured that stuff out?? It’s kinda like music. My favorite guitar player isn’t the best, fastest playing, highest selling, etc, but there’s just something about the way he puts himself into his art that resonates with me. From another long time MG fan, enjoy Death Stranding!!